Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Episode 8: Love Ahoy! How OKCupid Tested Anchoring Bias – Show Notes

In 2014, OKCupid revealed they had conducted an experiment to test the effects of showing false compatibility rates to users. The experiment was designed to test whether their algorithm was truly generating more meaningful conversations. There were two stages of the experiment. First, they tested whether the users would initiate a message. Second, they evaluated how often that message would turn into a conversation, at least four messages back and forth.

To do this, they structured user pairs that had a 30%, 60%, or 90% true compatibility, per their algorithm. They showed some pairs their true compatibility rate and others they mixed. For instance, they showed 90% to users with a 30% true compatibility and so forth. The theory was that showing a different compatibility rate would set an anchoring bias for the users as to whether they should expect a good connection or not. This would impact whether they would connect at all.

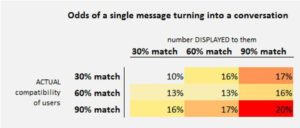

They found that showing a high compatibility generated more conversations, even if the true compatibility was lower, but not quite as many as if the true compatibility was high.

This proved that the anchoring bias had an effect and also proved that their algorithm was producing more meaningful conversations than a random ranking would. Success for OKCupid – right? Like many of these cases – yes and no.

Users were furious! They wrote tweets and emails to OKCupid demanding to know why they were experimented on – why OKCupid had toyed with their hearts.

Should OKCupid have had to state upfront that this type of experiment was a possibility? If so, would users even see it? Comment with your thoughts below.

Additional Links on OKCupid’s Experiment

OKCupid Lied to Users About Their Compatibility as an Experiment Forbes article detailing the results of the experiment and showing the text of the email revealing the true compatibility rates.

OKCupid: We experiment on users. Everyone does. Guardian article specifically calling out the OKCupid experiment as unethical. It also cites tweets from a sociologist who called on OKCupid to have an ethics board to review plans.

Episode Transcript

View Episode TranscriptMarie: Welcome back to the Data Science Ethics Podcast. You have Marie and Lexy here and today we’re going to be talking about the case where OKCupid ran a test and they didn’t necessarily tell people what they would have been expecting to hear.

This quick take goes to OKCupid, which is a dating site that really focuses on using data science and analytics to pair people up. Just like any dating site, they’re trying to match people but they really take the approach of data first for finding true love. Anybody that’s interested in data – going to their website and going through kind of their methodology is very interesting.

To make sure that their algorithm is doing what they want it to, they do tests and they see if the algorithm is actually pairing people how they would expect. One test that they did was they actually told people “you’re only a match with this person maybe 30%” when actuality they knew that it was more like a 90% match. They want to see if people would still reach out and even if they were telling them that the person was lower match if they would still be like “no, that person still looks pretty interesting. I would reach out to them anyway.” And then vice versa – something that wasn’t really good match saying “hey, this person that’s only actually 30% were going to tell you it’s 90%” and seeing if they would actually still reach out, start a conversation, try to build a relationship.

They were doing this as a way to see if their algorithm was matching people correctly and how people would actually respond during the test. So Lexy, do you want talk little bit more about what they found?

Lexy: They did this as a structured 3×3 cell test where they had people with a low, medium, and high degree of matching. Low was 30%, medium was 60%, and high match rate was 90%. So if they thought they were 90% compatible they would be considered a “high.”

In the test, they actually kind of shuffled it. Some people they kept at the original percentage that they calculated, others they adjusted artificially. That’s where they would tell someone who was maybe a 90% that they actually had a 60% compatibility or 30% compatibility or any combination thereof. They then looked at whether those people initially reached out and then, also, if they continued to converse four times. So they had to have had back and forth messages four times.

What they found was that the odds of sending one message went up a little bit depending on how much they showed the match rate to be. But the odds that they sent four messages, given that they sent the first message, were almost double if they showed that they were a 90% match even though they were actually a 30% match.

It really speaks to what we talked about in the last episode which is anchoring bias because they’ve provided this piece of information, that they’re highly compatible, as a starting point to this communication – to having people reach out. And as they continue to see if that’s true as these two people communicate, if they really do feel 90% compatible, it’s testing that first piece of information. But because they were initially told that they’re a high match rate, they absolutely continued to message more.

Marie: So then if they had that anchoring bias from OKCupid that this person is a 90% match even, though they only had 30% compatibility in OKCupid’s true algorithm, because they had the anchoring bias – because they had this perception that they were 90% match, they were much more likely to continue to do the conversation.

Lexy: Yeah. They were more likely to reach out and they were more likely to pursue it thinking that they should. It’s interesting because there’s a certain amount of speaking of a confirmation bias. A confirmation bias is when you have a perception of something and you want to find information that confirms that perception. How many of those conversations were people looking to see how they were compatible? How they were so much more compatible than it seemed to be – or if they actually were relatively compatible. Who knows?

The news of this particular experiment came out not long after another very famous experiment that Facebook had done. The real ethical dilemma that happened here kind of was two-fold. One is they didn’t tell people in advance that they were doing this.

After the experiment was over, they sent an email communication to those people who had connected. It indicated to them “hey, by the way there, was a glitch in the algorithm that caused it to accidentally tell you that this person was whatever percent compatible. The true compatibility is this other percentage. This has been resolved now. Sorry for any inconvenience.” Didn’t actually say “hey, we’re experimenting on you.” It masked it in this software bug kind of language.

Marie: Which I think is also an interesting question because then it gives you actually another potential anchoring bias. If you had been pursuing a conversation with somebody that you would normally only have a 30% match with, you had thought it was 90% but then you get this email saying “hey, they were supposed to be 30%” – do you continue the conversations if they had been going well? Or do you say “I thought there was something weird. Yeah.” And you drop it.

So it’s almost like they did two experiments. We’re going to give you this anchoring bias and we’re going to take this anchoring bias away. What are you going to do?

Lexy: You know, I want that data. I want to see what happened afterwards. Unfortunately, it hasn’t been released, as far as I can tell.

The other side of that though was that, after this big kerfuffle with Facebook and the fact that Facebook basically got called on the carpet for having experimented on people, OKCupid’s co-founder, Christian Rudder drafted this blog post that basically said “look, everybody focuses tests on people. Just deal with it. You’re part of the internet.”

And that’s true… Being in marketing analytics and, I know, Marie, in content marketing it happens all the time. But we think of a lot of these tests as benign. How many content tests do you do in a week?

Marie: Yes, we’re all getting tested on all the time. From a marketing perspective, it’s usually, like you said, fairly benign. People are kind of okay with it.

Lexy: Or they’re completely unaware of it.

Marie: Very true.

Lexy: But this one, because they came out after the fact and said “hey, we were having this thing with our algorithm and we messed up. You should have actually been this percentage and said it was his other percentage,” there was a huge uproar.

There were people saying “oh how dare you experiment on my heart?” And “how could you do all of this?” And “it’s so difficult to find a good compatible person to start with. Why would you make it more difficult on us? We’re all seeking love. Why are you being so cruel?”

Marie: I think that also comes into the ethical question of – okay, so if you’re trying to find the best way to sell a pair of shoes, the ethical ramifications of that are fairly low. Whereas the ethical ramifications of people feel like you’ve toyed with their heart is on a much different level. So what are the types of things that you should consider before you run a test on people that might be searching for love in this case?

Lexy: Well true… but at the same time, how do you test your algorithms if you don’t ever have an opportunity to change things and see if it still does what you think it’s going to do? If you tell people “yep, we know this is exactly the percentage,” are you setting yourself up for a self-fulfilling prophecy? Especially in something like a dating site where, often, people will rank their results based on the compatibility percentage. If you always rate from highest to lowest on your compatibility percentage, you’re never going to see those people who are 30%. Even if they maybe did get it wrong – if the algorithm did get it wrong and that was somebody that you were actually compatible with – you never would have even seen them.

As the owners of the algorithm, as the caretaker of the algorithm, how do you get a chance to experiment on data – on people in the real world – without having structured tests like this to ensure that what you’re doing truly is producing incremental value? It is giving people a better match than they would have otherwise gotten if you just shuffled the mix, put them up on the site in no particular order, and said figure it out.

Marie: Here are some people… good luck!

Lexy: Yeah. Here are some people. You might like some of them. Don’t tell us if you don’t.

The ability to test – the ability to continually refine algorithms – is something that we’ve touched on before and there needs to be data that says yes or no. And sometimes the no has to be forced. People are not necessarily going to go on to a dating site and say “I think today I’m going to down-rank everyone I don’t want on here.” That’s generally not the way you’re going about it. You’re going for the yeses, not the nos. But, at some point, you’ve got to test for both.

Marie: We’ve also talked about, before, in terms of the data science process, that it’s not just building an algorithm – it’s also maintaining that algorithm and continuing to test and continuing to make sure that it’s doing what you expect it to do. So, on the one hand OKCupid was definitely following the data science process and making sure that its algorithm was doing what they expected it to and making sure that it was still behaving properly. But on the other side there are some things they could potentially do to make sure that it’s more clear and more fair and upfront what they were doing and letting people know that this is going to be happening or communicated it in some way and not just kind of brushing it under the rug as it was a glitch.

Lexy: Yeah. There’s a lot to the idea of transparency in algorithm development, and especially in experimentation.

Experiment ends up being a kind of dirty word. People don’t want to be experimented on. More often than not, when people are being experimented on, they’ve agreed to it somewhere. It’s usually buried in a lot of fine print in the legalese of terms of service. It’s those terms of service that often get completely blown past – people don’t read them. If you have to get to the end of it you take your mouse over to the sidebar, you drag it all the way to the bottom, and check the box. Very few people take the time to really look at what they’re agreeing to. That becomes the foundation of being experimented upon. This is what Facebook had it’s also what OKCupid had.

Because of these types of experiments coming to light, they’ve been more forthcoming about the fact that “we, the company, are going to run experiments. You may or may not be a part of them. By using our services, you are agreeing to being a part of them if and when we decide you will be. You don’t get to specifically opt in or out. It’s part of what you get for using our site.”

This one – I think because it wasn’t clear up front, it caused an uproar and now you’re seeing the backtrack going towards a more transparent set of services in terms where, upfront, when you sign up for the site, it will tell you “we gather your data. We’re going to experiment.”

Now, of course, there are additional regulations they have to follow that force them to say exactly how they’re gathering your data and what they’re using for.

Marie: And I think the other part about these types of experiments is, not only are they important to the data science process, but telling somebody that they’re part of an experiment can also impact the results. As the person that is in charge of data science and of taking care of an algorithm, you also have to think about how letting somebody know that they’re in an experiment could impact the results. So I think there’s a lot of things to consider in terms of finding the right answer for the situation that you’re in.

Lexy: Absolutely. It’s one thing to say that, in general, you may be part of some experiment. It’s another to say “here’s exactly the experiment that we’re going to be doing” and knowing that upfront.

In medical experimentation, there is a large set of informed consent practices that have to be obeyed. There’s a regulatory board they have to go through. Essentially, it’s a medical ethics board and a review process to officially designate that there’s an experiment. And they have to lay out for each person who is going to be part of that experiment exactly what’s going to happen, exactly where and when they can opt out of that experiment.

There are some exceptions and most of those exceptions are in psychology. From a psychological standpoint, knowing that you’re in an experiment changes your behavior in ways that, being in a medical experiment that’s not psychology, you may not be capable of. There are placebo effects, certainly. However, more often than not, your body is going to react to a specific treatment in a certain way. But with psychology, we can adjust our behaviors in different ways when we think we have to. And so, often, you don’t have to get the same type of informed consent for a psychological reaction.

In this case, it’s very much a psychological reaction – it’s an emotional reaction. They wouldn’t necessarily have to go through the same things. Instead, you get this sort of general “yes you might be part of an experiment some time. We’re not going to tell you when.”

Marie: Very true.

Those are the big things that we wanted to touch on when it came to the experiments that OKCupid ran and how that relates back to the anchoring bias that we have talked about on other episodes. Thank you so much for joining us for the Data Science Ethics Podcast. This was Marie and Lexy. We’ll see you next time.

Lexy: Thanks.

I hope you’ve enjoyed listening to this episode of the Data Science Ethics Podcast. If you have please, like and subscribed via your favorite podcast app. Join in the conversation at datascienceethics.com, or on Facebook and Twitter at @DSEthics where we’re discussing model behavior. See you next time.

This podcast is copyright Alexis Kassan. All rights reserved. Music for this podcast is by DJ Shahmoney. Find him on Soundcloud or YouTube as DJShahMoneyBeatz.

As someone that has met… well, more people than I care to admit via OKCupid, I never put much stock in the match percentages. Anecdotally I met at least 15 people >90% and they were generally letdowns. But also, I met my current girlfriend on it, so there is that. My solution would be for OKCupid to advertise an “opt-in” for gentle experiments. The site already offers minor benefits to those that pay a subscription fee. It could offer the same for free to those that opt in. This WOULD introduce self-selection bias to the experiment, but it would heavily… Read more »